28 June 2010

Book part 5

If you want the whole thing for your leisure hours, email or facebook me, and I'll send it in pieces as it gets done.

***********************************************

A quick scene now out of time, a different mind, Adam and Chloe are just kids, not even ten probably, in a movie theatre sitting on either side of their mother. They're both sleeping, but their mother, Lillian, is wide awake and staring at the screen, enraptured in whatever is happening there invisibly to us. Not sure why that scene is here except to remind you of the kids who these young people once were, and of the people they will one day be when they all wake up and suddenly, surprisingly and without much warning, find themselves to have become their parents.

If we fast-forwarded into the future, we might see Adam as the parent now, a child on each side of him sleeping on a couch as he sits engrossed in the same movie, his mother now so many years in the grave, just across the river and a little southeast of Meridian as the song says.

The cooks lounge around outside the dining tent, right next to the steps that lead into the kitchen trailer, and they're smoking cigarettes and drinking coffee. As they watch and smoke, watch and sip, people race up the hill towards the vans, gear dragging along behind them, or race from the vans back down to the dining tent, having forgotten something or other. The early folks already have their seats in the vans, or were standing outside the vans with the engines running, stereos going, heaters pumping full blast, doors open. Some of these around-the-van-people, those who aren't looking for something or stuffing gear in the half open back door, were just hanging around, hanging out smoking, talking. Alain and Francois walk slowly up the hill towards the vans, smoking and sipping.

Adam's lunch, which is four ham sandwiches on white bread, without condiment or garnish of any sort, and small three apples, is stuffed now into his woefully inadequate backpack which is too small, too flimsy, and not even remotely waterproof. By ten a.m. it will be soaked right through, as will his sandwiches, and by the end of the next shift it will be in tatters, the straps duct-taped together, a giant hole in the bottom of it, all the seams and zippers and hooks busting off and breaking apart but for now, at least, it's good enough. But barely. His water is in an old plastic four litre milk jug that will last a few more days before he has to scramble for a replacement. His feet are wet.

Hey buddy, Feral says to him, loping up the hill and looking as if this were his backyard and he were going to have a picnic. How's it going?

Meh, Adam says. Not very good, but I'll survive I think. Maybe.

You THINK, eh? He THINKS Wolf Boy, Feral says, turning towards the dog, which Adam had failed to notice up until now. He THINKS he'll survive, Feral repeats. He's not sure, though. Well, if you think you may not survive Adam, please be sure to let me know, so that Wolf Boy here can eat your remains.

Adam laughs weakly. Glad to help out any way I can.

Now listen here, kiddo. This is only Day TWO. There's lots of Days left. Day One probably was one of the worst days of your fairly short life. Day Two will probably be worse. And don't even get me started on Day Three. Wooooo-eeeeeee... It's gonna pretty much kill ya buddy. But after that, soon enough, they'll get easier. Trust me.

Yeah, so they tell me. Guess I'll believe it when I see it.

You hear that, Wolf Boy? He says he'll believe it when he sees it. But, um, how blessed are they who have not seen, and yet have still believed it, eh? Y'know?

What?, Adam says.

You'll get through, kiddo. Trust me.

Okay. Guess so.

Feral giggles then like a crazy person, shakes his hair to get some of the rain out, and then tucks it into his hood. They're at the vans now and Feral says yep, gotta work buddy and is off to stuffing people's gear into the back of the van, off to organizing, a quick chat with Roxie about stuff.

Some of the rookies stand around aimlessly, Magda, and Lyn among them having a quiet conversation, leaning up against the van. Adam looks at her for half a second, at Lyn, wanting to start a conversation, but having no clue what to say. He looks away.

You smoke, right?, she says to him. Got a smoke?.

He nods, says um, yeah, yeah, sure, and digs nervously, quickly, into his backpack for his cigarettes. The pack is soaking wet. Absolutely soaking wet. He groans. Oh, man, he says. Oh no. They're useless. Sorry.

Ah, no worries lad, Feral says, arriving back just then. Today's a good day to quit.

Adam says: The worst day to quit, you mean.

Just then, Doug and Hank arrive, Doug having noted this whole interaction. I have smokes, he says, and reaches into his fancy, rubberized, waterproof backpack, whips out a pack of cigarettes. He gives Lyn a handful and then lights one for her gallantly, nodding and winking as he does.

Thanks, she says half-heartedly, his charm already having begun to wear a bit thin on her.

No worries sweetie, he says. And then that was it. His charm was now gone, entirely and without faint hope of return.

As Doug goes around to the back of the van to stuff his gear in, thinking that he's done quite well in setting himself up with a girl on party night, Lyn looks at the eight or ten cigarettes in her hand. Here, she says, and gives half of them to Adam, and he says thanks but so quietly and looking at the ground that she isn't quite sure and says uh, you're welcome, no problem buddy and Magda sees this whole interaction, smiles to herself.

The areas around the vans is busy and active now. Dogs chase each other, a few of the more rambunctious guys push and shove and wrestle despite the rain, hoping to impress the ladies. Sal strides up the hill, cigarette dangling from his lips, a map in one hand, and he's squinting at it while talking into the radio that's in his other hand. He's talking to Padre, of course, who is somewhere far away already, having left camp half an hour before most people were even up for breakfast.

Sal hops into his truck, which is running, and takes off, music-sound muted behind mud-muddied windows.

Roxie jumps behind the wheel of her van, the other crew bosses behind the wheels of theirs, the doors all slam shut, everybody's in, and they're off. Another day.

26 June 2010

Of Light And Halfway Between The Gutter And The Stars

This past week, Thomas Kinkade, famed “Painter of Light,” found himself behind bars after an arrest based on suspicion of drunken driving (mugshot shown). That sad episode came on the heels of Kinkade’s company recently declaring bankruptcy to elude paying millions of dollars to parties defrauded by Kinkade’s company years before. A self-styled Christian, Kinkade’s decidedly un-Christian behavior in busines...Read the rest.

This past week, Thomas Kinkade, famed “Painter of Light,” found himself behind bars after an arrest based on suspicion of drunken driving (mugshot shown). That sad episode came on the heels of Kinkade’s company recently declaring bankruptcy to elude paying millions of dollars to parties defrauded by Kinkade’s company years before. A self-styled Christian, Kinkade’s decidedly un-Christian behavior in busines...Read the rest.

Tolstoy on teaching

. . . every teacher must . . . by regarding every imperfection in the pupil's comprehension, not as a defect of the pupil, but as a defect of his own instruction, endeavour to develop in himself the ability of discovering new methods. . .'

25 June 2010

Do you remember the theory of ranges and delimitation?

http://alabelforartists.blogspot.com/2007/05/theory-of-ranges-and-delimitation.html

José Ferrater Mora, my new philosophical love

Some philosophers stubbornly shun any statements even vaguely hinting at rational analysis or scientific procedure. What can rational analysis and scientific method teach us philosophers, they argue, about such an "irrational," "mysterious," and "unscientific" problem as that of death? I strongly disagree with such quibbling, and what I say throughout this book will, I hope, testify to my disagreement. On the other hand, some philosophers embrace the opposite viewpoint: they scoff at any statement about death which happens to be a more or less mature fruit of human experience or speculative reflection. I disagree no less strongly with the latter contentions, for I do not think that we can so easily dispense with such a rich source of knowledge as human experience and "speculation." In sharp contrast with all these prejudiced and, at bottom, nihilistic attitudes, I have tried to pay heed both to reason and human experience, to analysis and speculation. Only by bringing all of them together shall we be able to cast some light on our subject. As a consequence of this integrating or, as it will soon appear, "integrationist" viewpoint, I have also bypassed two quite similar tendencies. There are those who hold that the problem of death is meaningless. On the other hand, there are those who think that only the problem of death has some meaning. I myself believe that the problem of death has a very definite meaning, but that it is far from being the only philosophical problem enjoying this sinecure. It is one philosophical problem among many, but one which is central enough to make the philosophical wheels turn swiftly.

Thus, they tried to bridge the gap between the world of Nature—with all its "mechanical" properties—and the world of Mind—with all its "spiritual" characteristics, but they based their attempt on one of the following controversial assumptions: either they "constructed" the world of Nature on the basis of the world of Mind, and thus reduced the former to the latter, or else they advanced the idea that there is some kind of entity—"the Absolute," "the Idea"—which underlies both Mind and Nature.

24 June 2010

22 June 2010

21 June 2010

Daniel Lanois

--Along with his own albums, his work has been recorded by Emmylou Harris, Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, and others. In 1997 he won a Grammy with Bob Dylan for Time Out of Mind. And along with Brian Eno he's produced and recorded work by Peter Gabriel, Neil Young, U2's albums the Unforgettable Fire and the Joshua Tree, and a bajillion other people.

Born in Hull, QC in 1951.

If you take his song "Jolie Louise" as autobiography, his parents were francophones, his dad got laid off from his job at the mill and drank too much, mom moved with the kids to Ancaster, just outside of Hamilton, ON.

Anyway, he's freaking brilliant. This clip from the last few years, and is him doing his song The Messenger on Q, the CBC show.

Sadly, he was in a fairly serious motorcycle accident this month, and has canceled his show at Montreal's Jazz Fest.

20 June 2010

18 June 2010

???

17 June 2010

Luce Irigaray

16 June 2010

Philosoraptor

15 June 2010

12 gates

14 June 2010

12 June 2010

Sigmar Polke R.I.P.

Bloomberg News - Sigmar Polke, one of Germany's best-known artists, died last night from cancer at the age of 69, his dealer Erhard Klein said in a phone interview. Polke, a painter, graphic artist and photographer, was "one of the most important and most successful representatives of German contemporary art," German Culture Minister Bernd Neumann said in a statement. "He was a critical, ironic and self-ironic observer of postwar history and its artistic commentators."

11 June 2010

WAC Arts Awards Winners Announced

The winners will be announced at 2010 Mayor's Luncheon for the Arts on Friday, June 18.

Please join us at the Mayor’s Luncheon for the Arts on Friday, June 18 to celebrate the accomplishments of the nominees in all categories, and fete the winners of the 2010 Winnipeg Arts Awards!

For more information about the event and to purchase tickets, please HERE .

ARTS CHAMPION Award

The Arts Champion Award honours an individual or business patron that has demonstrated sustained support to the arts in Winnipeg.

The nominees for the Arts Champion Award are:

*Mid Canada Production, nominated National Screen Institute - Canada.

*MultiMedia Risk Inc., nominated by Freeze Frame, Video Pool Media Arts Centre, The Winnipeg Film Group, and WNDX Inc.

*Michael Nesbitt, nominated jointly by The Manitoba Opera, Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art, and The Winnipeg Art Gallery.

WINNER*The Winnipeg Foundation, nominated by The Winnipeg Folk Festival.

ON THE RISE award

The On the Rise Award recognizes the demonstrated promise of an emerging professional artist (in any discipline).

The nominees for the On the Rise Award are:

*Karen Asher, nominated by PLATFORM: centre for photographic+ digital arts.

* Meghan Athavale, nominated by Oliver Oike.

*Arlo Baskier-Nabess, nominated by Stephanie Ballard.

* Sienna Bauer, nominated by Jennifer Davis.

*Rosie Chard, nominated by Karen Shanski.

*Clint Enns, nominated by Hope Peterson.

*Max Fleishman, nominated by Yuri Hooker.

*Ingrid Gatin, nominated by Peter Roy.

*Jeanette Johns, nominated by aceartinc.

*Lyndsay Ladobruk, nominated by Liz Garlicki.

*Caroline Nicolas, nominated by Jane Petroni.

*Heidi Phillips, nominated by Rick Fisher.

WINNER*Mélanie Rocan, nominated by The Winnipeg Art Gallery.

*Daniel Roy, nominated by Glenn Buhr.

*Adam Smoluk, nominated by Juliette Hagopian.

MAKING A MARK award

The Making a Mark Award applauds an established professional artist (in any discipline), who is receiving critical recognition for excellence in art practice in Winnipeg and beyond.

The nominees for the Making a Mark Award are:

*K.C. Adams, nominated by The Winnipeg Art Gallery.

*Owen Clark, nominated by Jeff Kula.

*James Culleton, nominated by The Winnipeg Folk Festival.

WINNER*Yuri Klaz, nominated jointly by The Winnipeg Philharmonic Choir, Shaarey Zedek Synagogue, Winnipeg Singers, and First Mennonite Church.

*David Krindle, nominated by Jesse Wood and Councillor Mike Pagtakhan.

*Michael Nathanson, nominated by Theatre by the River.

*Michael Nicolas, nominated by Jane Petroni.

*John Racaru, nominated by Walle Larsson.

*Xiao-nan Wang, nominated by Dr. Hermann Lee.

MAKING A DIFFERENCE award

The nominees for the Making a Difference Award are:

*Michael Boss, nominated by The Winnipeg Art Gallery.

*Ardith Boxall, nominated by James Durham.

*Kier-La Janisse, nominated by Hope Peterson.

WINNERS*Ava Kobrinsky & Mitch Podolak, nominated jointly by Ali Hancharyk, Josey Krahn, Tim Osmond and Vivian Gosselin.

*Jordan Miller, nominated by The Manitoba Arts Network and Jolanta Sokalska.

*Danny Schur, nominated by Mayworks Festival of Labour and the Arts.

10 June 2010

book, part 4

If you pulled the view back a bit more you would see several small huddled crews just like this one, crews spread over kilometres of clear cut, each of them listening to someone or other say something or other about planting trees. There was a small crew around Roxie, who was pumping her fist and giving the rock and roll sign, and telling them things like you plant hard, and then you fuk'n party hard--that's the life, man! It's all about givin'er! It's why we're fuk'n here!; and Padre showing them how to keep a cache clean because there's nothing shittier in the world than a shitty messy cache I'm serious he says, half-way annoyed about this already but trying to be kind, and Doug who wasn't trying very much at all to be kind, who was in fact slightly irritated and was telling them about how to check their trees for quality but not really interested in teaching them much of anything so much as he was scoping out all the cute new rookie girls, and so on and so forth, Sal hurrying around speaking endlessly into radio, looking at compasses and maps as he planned things, meeting someone or other from the logging company, or meeting a government person in their dark denims and unscuffed work boots, spending long days driving around and not getting too terribly dirty but still working under great professional stress all the same.

Yet who are they all, these random groupings of rain-coated lonesome pilgrims, and how did they all end up here? We could start with all of their childhoods if you wanted, or start with their ancestries, things far back in time like trans-oceanic immigrations and their great-grandparents meeting completely at random one day in a Depression-era cafe in North Platte, Nebraska, but instead we'll just start with this small little microcosmic part of things, start with the group of them like a huddled flock of rain-weary sheep listening to Feral tell them how to dance between the rain drops and how to hear the blissful roar of nothingness.

Listen, he'd say. Do you hear it? Rowwwrrrr...

Adam John Smith then, twenty-two years of age at the point at which this story begins.

How did Adam get to be here? And how did he get to be living at all?

He was born on January 16, in the year nineteen hundred and something-or-other and now, presently, twenty-two years four and one half months, twenty-seven days and six and one-half hours later, he's an orphan--a sad thing for anyone to be, certainly--and here he is standing in the rain, listening to Feral.

Now let's think back to a different time, to him sitting in what seems to be a factory work-place lunch room, the kind of place with Pepsi and sandwich machines and a small narrow window at the far white-lit end, safety and motivational posters on the walls that showed a clean and well-lighted, safe and tolerant multicultural workplace, and a scruffy young guy in overalls mentions to the whole table that he's going tree planting. Went last year he says, through a mouth full of sandwich. Fuk'n loved it. Babes, parties, you name it, man.

Where you do that?, one of the guys asks him.

B.C., he says. North. It's fuk'n awesome. The work sucks, but like, the rest of it's great. Fuk'n ladies man, everywhere. Like even in the showers and stuff.

They all nod. Impressed, envious, the thought of all that naked young smiling well-lighted multicultural flesh.

Is it easy to get jobs?, Adam asks suddenly, and everyone at the table reacts with a bit of a jolt, giving us the sense that he's not exactly known as a talker around these parts.

Naw, well... you gotta know someone eh? Why? You wanna do it Smith?

Adam shrugs. Maybe, he says, and keeps eating a sandwich of his own, plain salami on white, out of a Wonder Bread bag.

Cut to a few years earlier even, and a younger-looking Adam is sitting across the desk from a mid-forties woman whose desk and unkempt appearance suggest a certain stressed out disorder, but with sympathetic eyes, and she's holding a file folder. Liz S. K-No MacKenzie, the nametag on her desk says.

Sitting in a chair beside Adam is a young girl--fourteen maybe, or fifteen.

Well, Adam, the woman says, if you choose it, you would become your sister's legal guardian. And if not, she would, ahem, become a ward of the province of...

Children's Aid, Adam says, interrupting her. Like a fucking foster kid. And then Sorry, he says, about the swear.

Um... oh, yeah yeah, no worries, she says. Her eyes are tired, but still soft with sympathy. Yes, she says, Children's Aid. But, uh, perhaps you and Chloe would like to discuss your options?, she asks, looking now at the girl.

There are no options, Adam says. We've talked about it. She's my sister.

Chloe?, the woman asks, and the girl nods.

I want to stay with Adam.

Okay, well, we'll begin the processes, and, uh, okay, we have your phone number here, so...

The phone is... we, uh... Adam looks down at the floor now, his certainty of a few moments ago having vanished.

It's okay, the woman says. It's fine, I understand. Your mother didn't have a lot of money when she, um, passed on? And my condolences, to both of you, by the way. I lost my mother too when I was young. About the same age as you, Chloe.

Chloe nods, mumbles something about thanks. Adam nods too, but doesn't raise his head, keeps looking at the floor, counting the purple threads in the otherwise grey-brown carpet, multiplying the number of threads in this one square by the number of squares the entire office will contain. Thirty-six hundred, he thinks to himself. And forty-two.

So perhaps we can arrange to meet again next week, the woman continues, let's say Tuesday?, and until then, we can... uh... She stops, her eyes edged with thought. Do you have any resources?, she asks. D'you have any food?

Adam keeps looking at the floor. Chloe says nothing.

Okay, the woman says, okay, no worries, so what we can do for now then is help you get started, and Adam, we can talk about some options for work for you, and maybe some emergency money and food for now and, uh, are you working right now, Adam?

He shakes his head, says to the floor: I'm in university. My first year.

I see, the woman says. Okay, well, we'll talk about your options.

I'll have to drop out of school and get a full-time job, Adam says, raising his head and looking at her.

Fade out here, and now Adam is sitting at the factory lunch-room table, the option of tree planting suddenly in front of him and then cut to another interior scene, a dingy-small downtown Winnipeg apartment, Adam and his sister sitting at a kitchen table with a young man a few years older.

We want to move in together, Chloe is saying, looking at Adam, and then at the other young man. David is his name.

We... well, I... I love your sister, man. I have a good enough job, I can help her out while she does school, and...

Adam nods, chuckles. You're asking my permission? How old-fashioned. Geez... of course you guys can move in together. They all find it hard to look at each other now, but there's a feeling of joy.

They pour three shots in three mis-matched glasses, throw them back with a cheers. Cheers!, they all say. Let's go to Neighbour's, Adam says. Let's get drunk! They all laugh, and then it's out the door and onto Sherbrook St., half a short busy block of traffic coming behind them off the bridge and before it pours out into Portage Ave. and the North End, all this mid-level first-world poverty of West Broadway and northside just across the river and the street from all this first-world riches, and then they're laughing into the doorway, a pitcher of beer suddenly in front of them with some more mis-matched cups and Adam, charged with the good emotion of it all tells Zen, the bartender and owner, tells him: Chloe's moving in with this guy. Isn't that awesome?

It is, Zen says, touches their shoulders, he's so happy for them, they're so happy, corner of Sherbrook and Wolseley, small and northern-cold city, the ice-grip of winter and expectations of more so heavy on it now for so much of the year like grip of frost now like grip of age and disease and the grave.

And then the work lunch table again, Adam nodding, thinking about this tree planting thing, about the possibility of money, of adventure, of going back to school next year, and then the interior of the dingy-fair downtown bus station with wall-grimy grey, its grime-tiled floors and grime-light, multiple generations scattered about talking, burgers and fries with the cheap plate-clatter of coffee at Sal's, the buzz of life in the air. Adam's bags are piled in a wagon they borrowed from some kids in the neighbourhood because David, Chloe's boyfriend is a funny hippie anarchist guy with tattoos and a weird hair-cut who works repairing bikes with the kids at the local drop-in centre, teaching 'em art and giving 'em food and stuff, all that kind of stuff. For sure. The two kids who lend them the wagon, Preston and William, they want to follow along with them, because it's their wagon, and because they know the beginnings of an adventure when they see one. Where's your parents?, David asks, and I dunno they say, somewhere. Okay, well, c'mon. They tag along, two Cree brothers all of eight and six years old probably, Preston and Willaim, it's hilarious, the whole thing.

You're gonna have fun, Chloe is saying, squeezing Adam's arm. Adam nods, smiles a little.

I guess, he says.

Good luck, man, kick ass, says David, and then they all hug and Adam hoists up his bags and heads for the bus, turning to smile back at them once, and they wave, and the two kids wave as well and then he's out the door and onto the platform and handing his ticket to the driver and the two kids still stand inside there with Chloe and David, still waving. He settles on board into a seat now, adjusts his pillow against the window and then waits, waits as the bus fills up and then with that small troop outside still waving to him, Adam feels the diesel-heavy rumble as the bus drones out like an awkward dinosaur onto Portage Ave., onto the road that's already marked here as Highway 16.

On a signpost in front of the University, across the street from the tiny art gallery where Adam had gotten drunk one night at some random weird music show where he didn't know anybody and then people had him in the basement doing shots of Jim Beam and playing a drum and everyone was roaring and smoking and playing some kind of instrument or other and red and blue lights were on and a woman was singing something in French and the music just kept going, pulsing, everything kept going, everything was yes, it was one of the most weird and extravagant nights of his life, right across the street from this insignificant little green light pole where the road was marked as Highway 16, also called the Yellowhead, a road that runs from Portage and Main to far-away ocean, a road across the whole west, across the plains and farms and foothills and mountains until misty-sad Prince Rupert, northern sea port of heroin and mystery, town of hobo villages and of green mountains that rise from the sea, place where the road ended in a small unremarkable parking lot and then emptied itself at last into the ocean, a small sign marking it there too, looking northward to islands and to Alaska. The end of Highway 16, the road that began just down the street from where Adam now sat on the bus that pulled out past the art gallery and past the city into the plains and the sky that was forever.

And then, exactly forty-two and one-half hours later, he's in Prince George--exhausted and bus-ride dirty, only a few dollars and some change from completely broke. But he's ready to be a tree planter, whatever the hell that means.

Lyn.

Toronto. Pearson International Airport. An attractive fifty-something woman with a haircut and outfit that looks like she has a bit of money behind her is talking to a younger woman who's in her early twenties--a serious happy face with small round cheeks, dark short hair and big dark eyes. Pixie-ish. She looks Italian, or Egyptian or something if you didn't know.

Now listen, the woman says, if you don't like it there, you can come home. We'll get you out. Now... She waves away the protest the girl is mounting and continues, now I know we've always taught you to work hard and I know you've always done it, and I know you want to do this because your brother did it, but you don't have to go through with this just to prove something, okay? At any time, if you need to get out of that god-forsaken bush camp of yours, you just let us know and we'll buy you the first plane ticket home. I don't care how much it costs. Okay?

Mom please. I'll be fine. I'll be fine. I'm tough.

Yes, well... you're not tougher than a grizzly bear.

Uh hmmmm...

They hug.

I love you. All I want is for you to be happy. And for god's sake Lyn be careful.

I love you too. And I will.

And with that, the young woman hoists her several large bags up and onto a cart, and pushes it along to join the line that waits to approach the ticket counter.

She gets to the counter and smiles, pulls out some I.D.

Evelyn Prince, she says to the woman. I'm going to Prince George.

And so just like that in so many different forms, so many different journeys begin--by bus, by car, by train, hitchhiking their ways up or down the only couple of roads that led into Prince George they arrived, a few thousand planters who descended onto this sleepy northern sub-arctic city like a swarm for a few brief weeks early each spring, turning it from a rough little pulp town into a mecca of sorts, a roadside chapel for travelers and pilgrims, for the penitents who had come here seeking something, or seeking to escape something, though maybe in either case they weren't sure of just what it was.

Nine hours and a few stopovers later Lyn arrives, claims her bags in an airport that's not much bigger or less grimy than the bus station in Winnipeg.

And now we see Feral hopping out of an old rusty-red pickup, grabbing his bags from the back, throwing them over his shoulders saying thanks for the ride, buddy. Wolf Boy gives one last quick sniff at the other dog in the back there with him, they wag their tails and then he leaps out too and lands softly beside Feral, stretches easily and yawns, and then the truck pulls away with a bleeeep. Hart Highway, a sign says, and another says Prince George Downtown. An arrow points to the left, says 2 km. Feral and Wolf Boy wait for a break in traffic, wait and then head across the road. Feral is wearing grey overalls and a hoody, green bandana, work boots and dark-ish hair. He has a beard.

We see Hank getting off a bus, too, Hank just a few blocks down hill from where Feral is now, we see tall, skinny, mustachioed Hank, straw hat sideways on his head, army pants and old brown sweater, giant backpack on his back with a shovel stuck in the straps like a rifle, corn-blue eyes squinted like a philosophical cowboy in some old western movie. He's done this a few times before, you can tell. He has the look of the seasoned traveler or sea-dog, someone who knows where he's going and how to get there, and what to do if he gets lost.

We see Lyn again, Evelyn, claiming her bags at the airport, struggling gamely to the front door with two on the cart and one on her undaunted back, dropping everything with a bit of help into open trunk of a taxi. The driver, an old grey-haired Croat or Serb or something, Slavic, eastern, helps her, smiling paternal and kind. She gets in the front passenger seat.

Hey buddy, she nods. How's it going? Can I smoke in here?

You sure can, young lady, the driver says. As long as you open the window.

She looks over at him, looks at the window, back at him. Got a smoke?, she asks.

Now something you must understand about Prince George in the springtime was that it felt like one of the last stops of whatever might be left of the American-Anglo wild west, a sort of gateway to some pagan wilderness that no longer existed.

And sure, of course, those weird little end of the world outpost type places still showed up here and there, dotted villages ports and oases, research stations and forts that marked the final end of where the endless outward push of humans had stopped, and beyond all these places the part of the globe still standing lost to us, plains that stretched forever past isolated cities of Siberia or villages edging on African savannah or Australian outback, collections of huts and nurse's stations clinging to far mountainous coast of Chile, spots where humanity dropped off into oceans of caribou tundra, seas of camel-sand, eternities of whale and walrus ice. (NOTE: Draw Isle de Kurguelen, Queen Charlottes, etc)

Here though, here it was wasn't quite like Prince George marked the end of where humans had pushed. It just felt that way and in some ways too, on the map at least, it looked like it. Because from here there were only two ways to keep going--there was the west, far west along Highway 16 and over the mountains, a fourteen-hour drive from here to ocean, or else there was north--big, empty, forbidding north, places like Arctic Red River and caribou herds, frozen Mackenzie Mountains and deep riverside mines.

The river flowed through town here too, the Fraser, thickful of salmon and giant river-birds of the north, whole congregations of them who dined down on sand islands by the pulp mills and who debated their endless arithmetics through the night.

There it was. Prince George. Home of Lumber Kings hockey and migrant loggers and mill-workers, home to vagrant northerners and sad young prostitute girls, haul truck drivers and miners and oil-rig men drugging themselves into oblivion on their days off, and a few other things too, no one knew quite what, but something, yes, definitely. Definitely something. Families, churches, a small and active university and art museum or two, and the river. Always the river. The nazified dementia of a serial killer or two, maybe three even, maybe more, many more, shadowy numberless creeps along the Highway of Tears. All those missing women and the forest, a feel of it in every note, every tone of things, a feel in the air and the accents and water, forest and our collective failings felt in a certain fixedness of gaze, in the colour of sun and configurings of clouds.

And here was Lyn among them now too, Evelyn Rose Marie Prince, a face that blended in better than most, Italian or Egyptian if you didn't know but here they all are, all of them, night coming on slow into morning, random adventurers camping out in their tents by the river, or sleeping five to hotel room, all of it ready now all that land so expectant and waiting, Ben the future cop and his good rugby friend from Kitchener sleeping in back of pickup under tarp and blankets and stars in a Prince George field, everything sensing the energy of this big and quick westward migration of springtime, the mountains sensing what felt like the whole world arriving all at once onto them now, the whole world all at once just going on and on-going on, going on.

09 June 2010

Book, part 3

This will be easier if you have a koan, Feral tells them all seriously. Several seconds of silence ensue, rain falling.

Uh... what's a cone?, one young man says finally. Scott says this.

Anyone?, Feral asks. Anyone? What's a koan?

Magda, with such a charmingly heavy Quebecois accent says It's, uh... like un... tree cone?

Diff'rnt cone, but thank you miss Magda. Anyone? Koan?

Magada again. No. Okay. Un... joke? Un ree-dle? Something to... she stops here, flustered, and blushes just a little, then blushes quite fully in fact, blushes quite red with her rain-wet cheeks, red above her yellow-wet rain-suit.

No no, Feral says, no you're doing faaaaab-u-lus-ment. Continue, je vous prie. I beg you.

She smiles broadly, but entirely self-conscious, eyes on the clear-cut, takes a deep breath, says: Okay, a koan is he that you say to praying and to... euh... deallumer? She looks here to Feral. Turn off, Feral says helpfully. Yes, she continues, to turn off your mind down, okay?

Yes, yes, Feral says, laughing good-naturedly. Yes, perfect. To praying. To turn off your mind down, as the lady says. To do so on the auto-pilot, or to do so on the no-pilot. Everything shutting off, right? Perfectly in the moment, and nowhere else, but not in the moment either. It's a mystery, I know, but that's how you plant. That's how you gotta plant. Otherwise, this job'll fuck'n kill ya. I swear it, man. I swear, it'll fuk'n kill ya.

And then he's hopping from one foot to the other, doing jigs and reels and singing jingles to demonstrate his points about microsite selection and water drainage, about soil temperature and about what he calls, shouting to them over his shoulder as he puts a tree in, about the yea-saying joy of planting, about how to hear nothing, eh?, and to plant nothing, and to, uh, to be nothing? Right? Y'know? Crazy talk, mostly.

And who knows, he says. Who knows. Maybe it isn't.

Buddy,..., um... one kid, brownish-blond dread-locks, so obviously from some big city or other, says. This would be Keith. Uh, uhmmmm...

Yes? Yes? What is it?

Uh... well... he chuckles nervously... well...

Well what, man? What? Good god, spit it out. We only have three christly months.

What does any of this stuff you're saying here, what does it have to do with planting trees?

Wha... Wha...? Feral looks at the sky, at the forest, at the ground, looks at Wolf Boy, seemingly astonished that anyone would even ask this question. What does it have to do with planting trees?, he sputters. What does it have to do with planting trees? Great jumping jesus, man! Fuck! It has everything to do with planting trees! Now, okay, now lookit old Sal down there, you see him running around looking all stressed out and important?

They all look down the hill to where he's pointing, at a determined orange figure who strides quickly up the road and away from them, and they all nod. The girl who answered his question about the koan though, Magda, a strand of curly reddish-brown hair plastered to her perfect face and her perfect neck by the perfect rain, she doesn't look. Sure, she throws a quick glance over her shoulder for appearances sake, but mostly she's just watching him. He notices, looks away nervously, awkwardly, then looks back, to see if she's still looking. Their eyes meet again for a second, and they both smile. Adam, cold and glasses-blurry, notices this and is annoyed by it, though he couldn't quite say why if you had asked him.

Now old Sal there, Feral continues, turning his eyes away from Magda and back to the group, re-composing himself, now old Sal he's, uh... he's got too much sorrow. Ha, ha! It's true, don't laugh--he's seen too way much to ever be happy anymore. Poor bugger. Some days that guy saw more crazy shit before breakfast than most of us will ever see in our whole freakin' lives. He was in some kind of war or something. A big hero I guess, I dunno. Saved a bunch of lives or won some medals or something? But anyway, plant with heart, that's his motto. Plant with heart. I agree. He always says that this is all you're gonna do for the next few months, right?, is eat and sleep and shit and plant trees. So you might as well learn to enjoy it, and do it with heart. I say that too.

He continues. The reality is that your lives are gonna be really hard and really painful for a long while to come, and they're probably gonna be lonely, too. That's just how it is. Embrace it, make it your ally, and then plant with heart. Get a koan, too... Hoummmmmmmmmm, he hums, fingers in the lotus position, eyes closed. Everyone laughs.

Adam is just watching and listening, shivering wet in his almost-useless raingear and his soon-to-fall-apart boots, trying to absorb all this too-much-at-once information the way his boots are presently absorbing the rain, and thinking to himself man, how the hell did I end up here? This was such a bad idea. This fucking SUCKS. Can I go home? Then he remembers--no home to go to, no money to get there. I'm stuck, he thinks. I'm stuck here. This is it. Fuuuuuuuuuuuck.

Feral continues, planting another tree, making sure everyone's eyes are all fixed right right directly on him again, seeing every detail of what he's doing: You'll learn to be dirty and to bleed, people, and if you want to, and I'm serious here goddamnit, I'm serious, you'll learn to forget every single thing you've ever known about anything. Which is good, because none of it matters anyway, and none of it will help you out here. He finishes planting the last tree and straightens up now, looks at them as he end his speech: Because unless you've been an alpine guide, an Olympic marathon runner, a prisoner of war, or a rice farmer in those, uh, those rice-fields of Asia, pretty much nothing you've done up until now could've prepared you for this. And I mean nothing.

Yes, he says, yes man. This is it. This it it. It's all happening people. All at once. Ha, ha! Wooooo!

And on all of them, shivering there and huddled together in various states of comfort and not, the rain falls on the just and the unjust, the rain just keeps falling without intent, relentless and without intent.

But lets back up here just a little: Who exactly was this Feral person, a person whose name Hank had felt the need to make the rabbit ears around? In fact, let's back up to the very beginning of our story, or to the end of it, someone running along yelling things into the rain. Why was he alive, this Feral person, and why was this surprising? I mean, why wouldn't he have been alive? Was he supposed to have been dead at one time or another?

And then right away that makes all of this seem foolish, because we know you can't take a story seriously when things are happening like the dead coming back to life. Because once you're dead you're dead, right?

And there's no coming back from that, right?

Anyway, I'll attempt to tell you this story as best as I remember it, though it's been so long now, and though know I'm not even getting all of the facts straight anymore, and maybe I've forgotten some things, or added others, or confused them with some other stories I might've heard once, some songs, movies, whatever. Anyway you have my notes, like I said, and if you feel the need at some point in the future to sort them all out and to attempt to tell this story properly, then go for it. But by then, my granddaughter, I'm sure you'll have stories of your own to tell.

I'm so old now baby, so old, which is so surprising to you young people, the idea that such a thing could ever happen, or especially that it could happen to you. The physical impossibility of death in the mind of the living someone once called it, and he encased a shark in clear plastic just to really make the point. But I've forgotten so many things now, which is okay I guess, since we all have to be allowed to forget things, or else we'd all go crazy.

So I don't know. I don't know. I'm sure of that much. But here's the start of this story, and the end of it too, Adam down the puddle-street cell-phoning that Feral's alive, that Feral's alive, Feral's alive...

Night-rain, slow yellow beauty of light-soft on concrete dark, all the muted-rain city-sound, the place and the moment where everything blurs and becomes one.

Adam has put his cell phone away now, he flags a cab down and gets in door closes a-thud, piano music and slow fade into darkness end scene one.

06 June 2010

fencing lessons as life lessons

the easier it looks, the harder it probably is to master

break everything down, then build it back up by understanding each piece and how they work together

learn to do it right, bad habits are hard to break – and they always catch up with you

salute and respect your opinion; fight a fair, honest and honourable fight

don’t rush, make them come to you; be ready, then move fast

the game is mental and physical: train for them both

sometimes you’ve got to take the hit

there will always be someone better than you – go for it anyway, you never know

there will always be someone worse than you – remember what it’s like to be that person

forget the score – if you don’t it leads to boasting or revenge, both are dangerous.

you’re going to sweat, your hair is going to get messy, the occasional bruise is likely but if you come out alive you’re going to feel mighty good.

05 June 2010

Dennis Hopper

Here are a couple of my all-time favourite clips of his work-- from Apocalypse Now, and from Easy Rider, which he wrote and directed.

Also check out the "could I have one of those Chesterfields now?" scene from True Romance.

02 June 2010

Family Tree of Vincent Van Gogh

The brother who ate prunes------------------------------- Gotta Gogh

The brother who worked at a convenience store ------ Stop N Gogh

The grandfather from Yugoslavia ----------------------------- U Gogh

His magician uncle -------------------------------- Where-diddy Gogh

His Mexican cousin ---------------------------------------- A Mee Gogh

The Mexican cousin's American half-brother ------------ Gring Gogh

The nephew who drove a stage coach --------------- Wells-far Gogh

The constipated uncle ------------------------------------- Can't Gogh

The ballroom dancing aunt -------------------------------- Tang Gogh

The bird lover uncle -------------------------------------- Flamin Gogh

The fruit-loving cousin -------------------------------------- Man Gogh

An aunt who taught positive thinking ------------------ Way-to-Gogh

The little bouncy nephew ----------------------------------- Poe Gogh

A sister who loved disco -------------------------------------- Go Gogh

And his niece who travels the country in an RV --- Winnie Bay Gogh

I saw you smiling . . . there ya Gogh!

01 June 2010

SERIALIZED NOVEL, part 1

I cannot promise that, a la Dickens and the great classics of the serialized novel, I will end every chapter with a kidnapping, disappearance, death, or earth-shattering epiphany. But I'll do my best.

*****************************************

Two Hundred Dollar Days, by E.L. Tempete

You must understand before any of this that, if in fact he really was dead, his body was never found, and so immediately so many of these things are cast into doubt.

Immediately so many possibilities open up of theory and mystery, so much space for misunderstanding to grow into rumour, and for rumour to grow into legend, and for legend to grow into myth.

But a slow fade in then, a city scene, to open things.

It's night-time, and it's raining.

Our senses are ready.

Begin:

Present Day.

It's raining, in a city, and it doesn't matter which one really since they're all more or less the same, but it might as well be Vancouver, Canada, because if you know anything at all about Vancouver, Canada, you'll know that it's always raining there.

Blur-colour hexagons through ghost-dark sheets of mist, the muted sound of cars, slow flow of traffic glowing its way into view. Strange things of magic could be afoot on a night like this even in a place as unmagical as Vancouver, Canada, because night-time and rain could sometimes bring those sorts of things out, turn ordinary streets into space of legend, ordinary rooms into halls for the imagination. Everything golden-orange around the edges then, thin yellow skin of streetlights on stone-wet darkness that blurs in everywhere, every doorway, rain falling.

And now, at the farthest back edge of our scene, a single human figure appears, running straight towards us, and we can see by his wild gestures that he's yelling something, though we can't quite hear it. He's even closer now, still coming straight towards us, and we can start to notice features--a man mid forties, pale with thinning grey-ish hair, clad in a dark-toned business suit. He's yelling still, and now we see that it's into a cell phone.

And then he flashes past us, water spraying up off him and onto our view-point shot and then FERAL'S ALIVE!, he yells.

Feral is alive.

But we laugh when we hear this, since there's only one fact in this story that is wholly and completely without dispute, only one incontestable shred of evidence that actually gives this all this some substance, and that fact is that body or no body, evidence or none, Feral Danger MacDuff, legendary legend, heroic tree planter of the Canadian North, is dead.

Very dead, as the saying goes.

Very, very dead.

Another dark screen and we fade in to the sound of rain falling again, since anyone who has ever planted trees for a living knows that it seems to rain an awful lot there too.

Right now all we see is a clear-cut, the rain coming down in slow motion. You take a mountainside that's chock full of trees, an old-growth forest that has sat undisturbed for all of time as far as we're concerned, and then you build a road through the middle of it, a couple of rough and gravelly things hardly fit to be called roads. And then, except for the odd moose hotel, you cut all of these trees down and haul them away, every single one of them pretty much, tens of thousands of them, or even hundreds of thousands in the space of several days, and there you have your basic clear-cut.

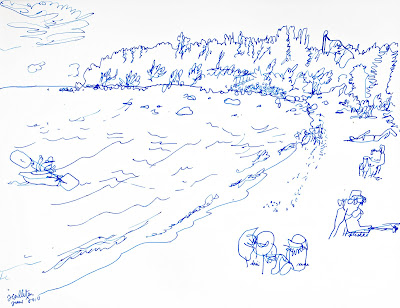

Exhibit A, then, is one completely random clear-cut in British Columbia, one out of the too-many-to-count, sometime in late spring or early summer. We can tell that it's B.C. because of the mountains, and we know it's late spring or early summer because this particular bit of land is turning a deep-heavy shade of green dotted by patches of wildflowers, by clusters of purple, yellow and orange that pock the otherwise vivid jade hillscape.

Now, you take a clear-cut in early spring, a week or so after the snow has melted, and it's just about the ugliest thing you can imagine. It looks like a graveyard. That got run over by a bulldozer. After a war. Dead tree stumps are everywhere, dead trees stumps and irregular gouges left by the metal-heavy machines, the whole mess of it strewn with piles of left-behind tree garbage, broken and uprooted trees dark against that sky. These piles, this scattered tree-limb stuff was called slash, and get used to that too. That and the rain.

But since it's no longer early spring, and now well into mid-summer, this whole big rainy clear-cut looks like the shimmering green sea-waves in some Japanese print, or like a quilt being shaken by the hand of some invisible giant.

Move our view a bit closer to ground-level now and a dog appears, a big grey-black husky sort of thing with a black mask over lean white-grey face. From our perspective he seems to just materialize, to take shape from out of the mist and the wind and the piles of slash. He's wet, and in our slow-motion view he's sniffing the ground and the air while the rain runs down off his fur.

Add music now, something dramatic, a monk choir singing hallelujah hallelujah pray for us now and in the hour of death amen.

And now two human figures come into view, also in slow motion, one from each side of the screen. We see no faces yet, only figures, a close up of a shovel striking downwards into the earth, then a shot of spray flying up everywhere, now a heavy spiked leather-black boot that digs into the mountainside, a flash of rain pants, a yellow coat-arm and glove, and now a pant that looks like it's made of cowhide, a true rain slicer of the old sea-dog sort, then our view pulls back up and cuts to real time boom their shovels drop into soil at the same instant, a tree seedling rough-slid by a set of wet muddy duct-taped fingers along shovel blade into hole, orange boot kicking it shut as fingers, so unbelievably dirty and ragged-looking, tug at top of tree and then all moves on slowly, slowly, same series of movements over and over as they work gradually up the mountain and away from us onwards, forever upwards into the rain. Hallelujah, the monk-choir would keep singing, hallelujah, pray for us now and in the hour of death amen.

Visible like rock-islands in the ocean of otherwise green are thousands of tree stumps in every direction, stumps up the hill, stumps down the hill, across the hill, everywhere just whole rolling fields of them, sad muddy roads and big dead slash-piles dividing all into irregular-shaped chunks of land. The forest hemming it all in.

A block, it was all called, this collective and human-generated ecosystem.

Or, more accurately, The Block, an unconscious capitalizing of the two words.

Pull our view back now and they're just two small specks, only yellow rain coat showing up at all, and in every other direction around is more mountains and clear-cut hillsides shifting in and out of mist who curtains it all in, sweeping vistas of trees and far-below valleys and forever, forever eternity of rainclouds, endless grey rain.

Two years earlier.

It's raining again, a different clear-cut somewhere else now...